Chapters 2 and 3 - The Process of Exchange and The Circulation of Commodities

- Nov 21, 2017

- 10 min read

Joel, reporting back here from the second session proper on Chapters 2 and 3.

Chapters 2 and 3 are similarly dry, most technical, writings. As Naomi pointed out, I did say that getting past Chapter 1 was the hardest part, but, to be perfectly honest, I was mistaken. I think I meant to say Part One (which is made up of Chapters 1-3) rather than Chapter One! Oops!

I'll very briefly summarise the content of these two chapters.

In Chapter 2, Marx begins by making a point that reveals the deeply structural nature of his whole theory. He says:

'It is plain that commodities cannot go to market and make exchanges of their own account. We must, therefore, have recourse to their guardians, who are also their owners. Commodities are things, and therefore without power of resistance against man. If they are wanting in docility he can use force; in other words, he can take possession of them. [1] In order that these objects may enter into relation with each other as commodities, their guardians must place themselves in relation to one another, as persons whose will resides in those objects, and must behave in such a way that each does not appropriate the commodity of the other, and part with his own, except by means of an act done by mutual consent. They must therefore, mutually recognise in each other the rights of private proprietors. This juridical relation, which thus expresses itself in a contract, whether such contract be part of a developed legal system or not, is a relation between two wills, and is but the reflex of the real economic relation between the two. It is this economic relation that determines the subject-matter comprised in each such juridical act. [2] The persons exist for one another merely as representatives of, and, therefore. as owners of, commodities. In the course of our investigation we shall find, in general, that the characters who appear on the economic stage are but the personifications of the economic relations that exist between them.

In order to be able to exchange commodities for their exchange values, there has to be private property as legal institution. But, private property is, therefore, a 'juridical relation' that is secondary to an 'economic relation' (commodity exchange). Here's the key bit - the buyers and sellers of commodities are 'but the personifications of the economic relations that exist between them'. What Marx seems to be saying is that we think we're the subject (the agent) of our economic activities, but, in a way, we're actually the objects. Much more on this later!

Marx goes on to talk about the historical origins and emergence of commodity exchange and of money. Here he totally debunks Adam Smith's founding myth, which has come to serve as the founding myth of Economics and, therefore, since we live in the world of economism, our contemporary capitalist society.

Early into his Inquiry into the Wealth of Nations, Smith asserts that 'every man' has the 'propensity to truck, barter, and exchange'. He's trying to do (at least) two things here. First, he's trying to explain how the 'division of labour' into countless forms of human labour emerges. Second, he's trying to 'naturalise' the market society by saying how we're all wheeler-dealers by nature. This is going to lead on to Smith insisting that, though we all act out of our own self-interest, the miracle of the market is that self pursuits are translated through the market mechanism into optimal social outcomes. Smith's infamous religious analogy is that of the market's 'invisible hand'.

For Smith, 'primitive' or 'savage' society is made up of atomised, trading individuals who exchange labour with each other - I'll swap you 10 arrow heads if you fix my roof. That kind of thing. The problem here is that there has to be a 'double coincidence of wants' for there to be an exchange, i.e. I've got to want arrow heads at the same time that you have to want your roof fixing'. This is how money is 'invented' as a social institution to facilitate general and generalised exchange.

This is genuinely the founding myth of economics and that means it's the founding myth in the creation of 'homo economicus', the idea of 'economic man'.

That means that this is the myth deep at the heart of the capitalist transformation of not just our society, but our very souls. Think I'm exaggerating? Ask Margaret Thatcher! Don't worry! I'm not summoning her spirit out of Hades. Check out this quote from an interview in 1981:

'What's irritated me about the whole direction of politics in the last 30 years is that it's always been towards the collectivist society. People have forgotten about the personal society. And they say: do I count, do I matter? To which the short answer is, yes. And therefore, it isn't that I set out on economic policies; it's that I set out really to change the approach, and changing the economics is the means of changing that approach. If you change the approach you really are after the heart and soul of the nation. Economics are the method; the object is to change the heart and soul.'

The problem of Smith's account is not just moral; it's factual. In David Graeber's magisterial Debt: The First 5,000 Years, Graeber scours the archeological and anthropological records looking for Smith's individualistic traditional societies based on internal market exchange. Guess what! He can't find a single example. Instead, the record is far closer to Marx's account here that relations of production, exchange, and consumption are unified in use-value, i.e. people collectively produce for their own collective use, and that exchange (trade) occurs on the margins of their community with outside groups. As trade grows, production for trade (commodity production) grows, and very gradually an 'opposition between use-value and value' coheres. Then...

'... [t]he need to give an external expression to this opposition for the purpose of commercial intercourse produces the drive towards an independent form of value, which finds neither rest nor peace until an independent form has been achieved by the differentiation of commodities into commodities and money. At the same rate, then, as the transformation of the products of labour into commodities is accomplished, one particular commodity is transformed into money.'

This, for Marx, is how 'money necessarily crystallizes out of the process of exchange' as commodity exchange becomes widespread and generalised.

The rest of Chapter 2 is taken up with Marx explaining why money takes the form of gold and silver. It's basically because of the uniform quality and divisibility of these precious metals. The metals are divided by weight and standardised and this is where the names of very many currencies originate from, e.g. 'Pound'. It may start as literally a 'pound' weight of gold, but the currency name doesn't stay tethered to this weight for long. A lot of Marx's exploration of money in Chapter 3 is concerned with how money gradually moves further and further away from these golden foundations - from gold to baser metal coins to paper to credit-money (IOUs, bonds) and, though he doesn't go this far here (see vol 3), into financial instruments. Money is trying to break away from the bonds of the human labour whose value it must ultimately express. Financial crises - when asset bubbles blow up and burst - have much to do with this Icarus-like adventure. Later in Chapter 3, Marx also points out how state power is integral to establishing the 'objective social validity' of money.

Chapter 3 is tough. I'll just pull out a few key themes. Marx brings in the issue of price. Commodities have prices. These prices go up and down with varying speeds and volatility. Marx is eager to clarify that PRICE ≠ VALUE...

'The possibility, therefore, of a quantitative incongruity between price and magnitude of value, i.e. the possibility that the price may diverge from the magnitude of value, is inherent in the price-form itself. This is not a defect but, on the contrary, it makes this form the adequate one for a mode of production whose laws can only assert themselves as blindly operating averages between constant irregularities.'

This divergence between price and value is necessary for the market mechanism to function.

A second theme, really central to the whole book, is that of movement. Marx is setting out the process of circulation here. The circulation process goes like this:

C-M-C where C=Commodity and M=Money.

You have a commodity you don't want/need to sell. You sell it in the market for money.

You use the money to buy something you want/need.

Marx talks about a 'metamorphosis' as commodities exchange for money and then new commodities. He reminds us that this is only possible because:

'When they thus assume the shape of values, commodities strip off every trace of their natural and original use-value, and of the particular kind of useful labour to which they owe their creation, in order to pupate into the homogeneous social materialization of undifferentiated human labour. From the mere look of a piece of money, we cannot tell what breed of commodity has been transformed into it. In their money-form all commodities look alike '

So, after the C-M process, there comes the M-C. Here, Marx reasserts the deeper, hidden nature of money he has uncovered as 'the absolute alienable commodity because it is all other commodities divested of their shape the product of their universal alienation. So, in the M-C process, money confronts all the commodities in the marketplace as the great total power, but a power with limits because those all the commodities' prices cast 'wooing glances' at money, they also 'define the limit of its convertibility, namely its own quantity'.

A third theme is that of contradiction and crisis. Commodity exchange and circulation is rife with internal contradictions: use vs exchange value; concrete vs abstract labour; private vs social labour; commodity vs money; buyer vs seller, etc. For the first time in Capital, Marx points out that its the 'antithetical phases of the metamorphosis of the commodity' (i.e. C-M and M-C) that express these contradictions and that 'these forms therefore imply the possibility of crisis. More on this theme later too, of course!

Actually, there is something else important about crisis here. Very briefly, I want to point out that it's in Chapter 3 that Marx refutes 'Say's Law', i.e. the assertion first put forward by early 19th C French political economist Jean-Baptiste Say that supply creates its own demand. This means that you can't possibly have a glut caused by overproduction cos anything you produce will find a buyer.

'Nothing could be more foolish than the dogma that because every sale is a purchase, and every purchase is a sale, the circulation of commodities necessarily implies an equilibrium between sales and purchases...No one can sell unless someone else purchases. But no one directly needs to purchase because he has just sold.'

Sorry, Tom! No guarantee you'll sell all your lemonade!

Marx moves on in this chapter to explore a quantity theory of money, i.e. how much money is needed in an economy to make the world go round? I won't go into this. Suffice to say that it depends on how rapidly currency is circulated and how much is held back in reserve in savings to grease the wheels of investment.

The final point of great important relates to the passage concerning hoarding in relation to accumulation. This is the first mention of accumulation in the book and Marx has the following to say:

'The hoarding drive is boundless in its nature. Qualitatively or formally considered, money is independent of all limits, that is it is the universal representative of material wealth because it is directly convertible into any other commodity. But at the same time every actual sum of money is limited in amount, and therefore has only a limited efficacy as a means of purchase. This contradiction between the quantitative limitation and the qualitative lack of limitation of money keeps driving the hoarder back to his Sisyphean task: accumulation. He is in the same situation as a world conqueror, who discovers a new boundary with each country he annexes.'

This is a crucial passage. Money is the universal representative of material wealth (a quality), but money is always expressed as a finite sum (quantity) with a finite power of purchase. This means that, unlike any other commodity, the drive to hoard and accumulate money is infinite. It's a 'Sisyphean task'.

Marx ends the chapter with a characteristically poetic passage describing how money is master in capitalist society:

'Whenever there is a general disturbance of the mechanism, no matter what its cause, money suddenly and immediately changes over from its merely nominal shape, money of account, into hard cash. Profane commodities can no longer replace it. The use-value of commodities becomes valueless, and their value vanishes in the face of their own form of value. The bourgeois, drunk with prosperity and arrogantly certain of himself, has just declared that money is a purely imaginary creation. ‘Commodities alone are money,’ he said. But now the opposite cry resounds over the markets of the world: only money is a commodity. As the hart pants after fresh water, so pants his soul after money, the only wealth.51 In a crisis, the antithesis between commodities and their value-form, money, is raised to the level of an absolute contradiction. Hence money’s form of appearance is here also a matter of indifference. The monetary famine remains whether payments have to be made in gold or in credit-money, such as bank-notes.'

All this hard work (of writing and reading) sets us up for Part Two of the book when we explore how value is produced and what capital really is! Stay tuned!

As for the discussion that these chapters prompted, what was wonderful to behold for me was the variety in the issues raised. There was particular interest in the story of an American young woman selling her virginity to the highest bidder, the winner being an Abu Dhabi businessman who paid $2million!! It was great to see everyone connecting the themes of the chapter to real world issues.

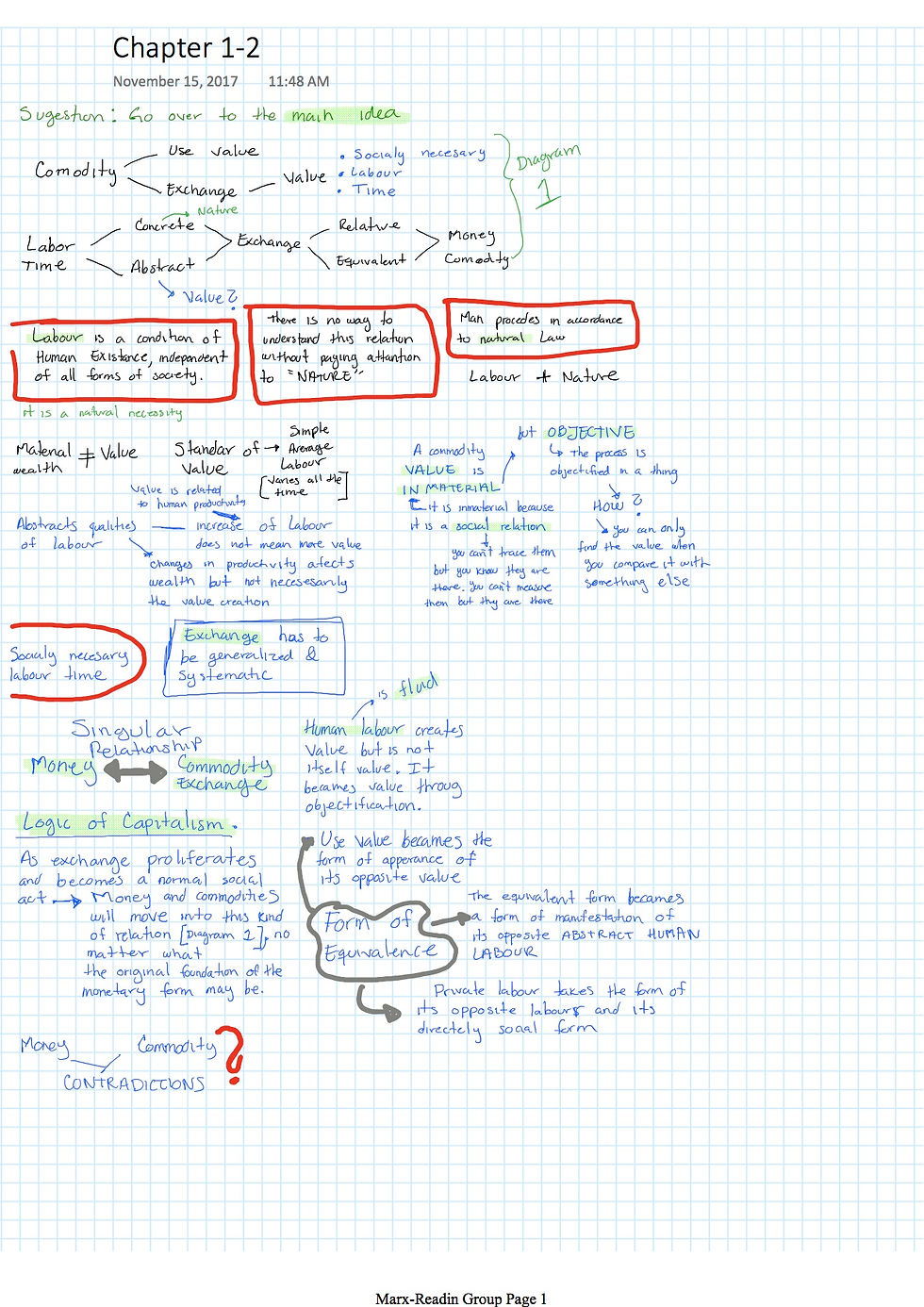

Before I sign out, I want to share with you the notes of Dulce Rodriguez, one member of our group. Her notes are very clear and beautiful and we hope they are of interest and use to others.

Finally, see below for the questions raised by group members this week. We hope that reading the rest of the book will shed light on them.

Thanks for reading

Joel

What does Marx mean by ‘contradiction/s’?

When we save money how does it affect the C-M-C circulation?

You have to deal with the reality and what is underneath – fetishism (real abstraction, imaginary, ideal)

At start of Ch2, use-value for owners and others. Why is something valuable to someone? Who decides?

‘Shadow value’ – land valuation (gentrification?)

Money, value, and state power?

Transparent supply chains? Corporate social responsibility? Is it enough? Does it work?

Overproduction and waste – Why? What is the potential role of technology, of government?

What about ‘really existing’ socialist experiments, governments?

How does the Bristol Pound work?

Comments