Chapters 4-6: The Transformation of Money into Capital

- Nov 28, 2017

- 13 min read

Before our meeting to discuss Chapters 4-6 on Friday afternoon, I met Dulce Rodriguez, one of my co-readers outside our meeting room. She told me that, while reading the first five chapters of this book, she kept asking herself why this book and its author were so demonised and controversial. There was nothing much yet in its mostly technical, dry prose to uphold all those pejorative characteristics of Marxism she had been exposed to. By the end of Chapter Six, 'The Sale and Purchase of Labour-Power', however, all became apparent...

The story so far...(skip this if you've got it!)

Marx has started out with the commodity and has said how the commodity has an internal contradiction between its use-value (what people want to use it for, what its function is in the wider process of social reproduction) and its exchange-value (what it can be traded for). He says that for commodities to be exchangeable, there must be something universally present within each and commensurate among all. He says this is abstract labour - the amount of average socially necessary labour time (SNLT) needed to produce a given commodity.

He then spills a lot of ink talking about the historical process by which production for exchange value grows, by which the rupture between use value and exchange value and, hence, the development of commodity exchange emerges, by which the need for a commodity functioning as 'universal equivalent' generates the circulation of money - first as gold, later as coin then paper then credit. He then talks a great deal about commodity exchange being a process of circulation along two separate and antithetical circuits: C-M-C and M-C-M'.

C-M-C is the circuit oriented towards use-values. A possessor of a commodity with a use-value she does not want/needs to sell exchanges it for money - the universal equivalent - in order to purchase a commodity of the same value with a use-value she does want/need.

M-C-M' is the circuit oriented towards exchange-value. A possessor of money advances some in order to purchase commodities to be used in the production of a new commodity which will be sold at market for a sum greater than the original advanced sum.

'The path C–M–C proceeds from the extreme constituted by one commodity, and ends with the extreme constituted by another, which falls out of circulation and into consumption. Consumption, the satisfaction of needs, in short use-value, is therefore its final goal. The path M–C–M, however, proceeds from the extreme of money and finally returns to that same extreme. Its driving and motivating force, its determining purpose, is therefore exchange-value.'

The question that Marx addresses, finally directly (!), in Chapters 4-6 is this: 'how can it be that the possessor of money gets more money back at the end of this circulation process?' or, put more simply, where does profit (or, in Marxian terms, 'surplus value') come from?

Before he addresses this question directly, he has some very important things to say in Chapter Four regarding the nature of capital.

As opposed to the 'simple circulation of commodities' for use-value (C-M-C), 'the circulation of money as capital is an end in itself, for the valorization of value takes place only within this constantly renewed movement. The movement of capital is therefore limitless'. Here, Marx is emphasising that definition of capital as 'value in motion'. Once profit is realised on sale, if the money (or at least part of it) is not reinvested in another round of accumulation, it ceases to be capital and is just money. And so the aim of every, any capitalist must be:

'...the unceasing movement of profit-making.8 This boundless drive for enrichment, this passionate chase after value, is common to the capitalist and the miser; but while the miser is merely a capitalist gone mad, the capitalist is a rational miser. The ceaseless augmentation of value, which the miser seeks to attain by saving his money from circulation, is achieved by the more acute capitalist by means of throwing his money again and again into circulation.'

But, this is where Marx takes us deeper into the structural nature of his argument. It is not the capitalist or even the class of capitalists who are the agents in control of this process, he suggests. Instead...

'In truth, however, value is here the subject of a process in which, while constantly assuming the form in turn of money and commodities, it changes its own magnitude, throws off surplus-value from itself considered as original value, and thus valorizes itself independently. For the movement in the course of which it adds surplus-value is its own movement, its valorization is therefore self-valorization [Selbstverwertung], By virtue of being value, it has acquired the occult ability to add value to itself. It brings forth living offspring, or at least lays golden eggs.'

He goes on:

As the dominant subject [übergreifendes Subjekt] of this process, in which it alternately assumes and loses the form of money and the form of commodities, but preserves and expands itself through all these changes, value requires above all an independent form by means of which its identity with itself may be asserted. Only in the shape of money does it possess this form'

So, what Marx is saying is that not we humans, not capitalists, but value itself, is the 'dominant subject' of this process of endless accumulation, that value therefore valorises itself through our activities, and that, though it continuously changes form between commodities and money, value's identity is realised and asserted in and through money. This is crazy stuff! No surprise that Marx uses terms here and elsewhere like 'occult' and 'magic'.

The first thing to say here is that Marx does not use these terms literally. He's using them ironically to mock bourgeois classical political economy which is stuck in the reified, superficial world of appearance - the realm of commodity exchange, the marketplace - and which, as we'll shortly see, has no theory to explain how money can beget more money.

The second thing to say is pretty damn deep...

In our session, we took some time to discuss this issue. Lauren said how it reminded her of John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men and the way that forces beyond the novel's protagonists' control left them unable to live the modest life they dreamed of. Dulce wondered what this said about human nature: does it mean that we are all greedy and selfish or, at least, made this way by an external force of our own making? She spoke of how the generosity and solidarity she encountered in the poorest parts of Mexico gave her hope. She spoke of this as a 'natural' way of being, of living. I agreed. I contrasted Charles Darwin's interpretation of the evidence of evolution he was confronted with to the work of Petr Kropotkin and other Russian biologists working at the same time and later in the 19th Century. Darwin's emphasis on competition surely derived from his own social background. He was the son-in-law of leading industrialist Josiah Wedgewood. His evolutionary theory sat well within a bourgeois ideology and, of course, a crude and reductionist version of Darwinism has been used to legitimate and naturalise capitalist society since. Kropotkin, on the other hand, resisted Darwin and Darwinism and shifted the evolutionary emphasis back onto what he called 'mutual aid'. It's co-operation, not competition, that is the fundamental factor in determining the evolutionary prospects of any life form, of life itself: from microbes to human beings.

So, yes, mutual aid - mutual support, co-operation, reciprocity - is natural. But, we can't then just say that the oppressive, exploitative, and violent nature of capital (and really existing forms of communism) are somehow external - that value is some kind of alien force. No! We must accept that capital is just as 'natural'. My embryonic theory here is that we need to bring theories of evolutionary consciousness and mystical philosophies of monism in here.

For consciousness to evolve it needs to begin to see itself as consciousness - this, we think, separates human from animal consciousness: we are conscious that we are conscious. But, to do this, there need to be a separation. An ego must be formed that can see itself. The danger then becomes that this ego starts to delude itself that this separation is real, i.e. that there is a separation between subject and object, seer and seen. This is the separation that tears asunder the oneness, the unity, of life. This is the separation that leads the bearers of this ego - us humans - to conceive of God as 'out there', of Nature as 'out there', of others as 'out there'. It is the separation that makes exploitation, domination, and violence possible and, tragically, real.

Perhaps we can see the 'dominant subject' of capital as the material force caused by this initially metaphysical separation - the contradiction that gives birth to all subsequent contradictions and the initial alienation that breeds a whole system of subjective, social, and natural alienation? Perhaps...

Anyway, sorry for that metaphysical rumination there! Back to main question at hand, addressed now in Chapters Five and Six: where on Earth does this extra money come from?!

Now, remember that the subtitle of this great work is 'Critique of Political Economy'. Before he can offer his great revolutionary answer, Marx has to do a job on the classical 'vulgar' bourgeois classical political economists who have come before him. Marx gets stuck into a bit of 'immanent critique' - He seeks to take his former bourgeois political economists at their own word, to take their theories to their logical conclusions, in order to disprove and disarm them. And so we have to wait a fair while while Marx comprehensively does a hatchet job (!) on their theories. This is what he does in Chapter Five...

The bourgeois political economists say that exchange is and has to be the 'exchange of equivalents'. Why would you knowingly trade your corn for linen of less value? You might think you're getting more for your trade, but the trade would occur then only when your partner was equally convinced of the same thing. Some political economists (Marx cites one Condillac) actually thought profit came from each trader thinking they had got more for less. Others say more directly that it comes from sellers overpricing their goods. But, as Marx has pointed out, we're talking about circulation processes here in which buyers become sellers become buyers, etc. So, if you're selling at 10% over value, you're also buying! This leads Marx again to insist that;

'If commodities, or commodities and money, of equal exchange-value, and consequently equivalents, are exchanged, it is plain that no one abstracts more value from circulation than he throws into it. The formation of surplus-value does not take place.'

Marx then goes on to disprove Malthus' and others' theory that there must be a separate class of consumers - landowners, clergy, other hangers on - whose social function it is to consume like crazy to keep the system going. But, where do they get their money, 'whether by might or by right', continuously from that is outside the general circulation of commodities and money, asks Marx? They plainly don't! And so...

'However much we twist and turn, the final conclusion remains the same. If equivalents are exchanged, no surplus-value results, and if non-equivalents are exchanged, we still have no surplus-value. Circulation, or the exchange of commodities, creates no value'

It's the same for 'usurer's capital' or what we'd call 'finance capital' today. Even in the M-M' (that is, money-more money) circuit, money does not simply magically lay golden eggs!

Does it occur outside of the circulation process, ask Marx? No! When someone turns their leather into boots, they don't realise the extra value unless and until they've sold those boots in the market. This leads to a curious impasse:

'Capital cannot therefore arise from circulation, and it is equally impossible for it to arise apart from circulation. It must have its origin both in circulation and not in circulation. We therefore have a double result.

Marx's job of immanent critique here is done. He has shown, most persuasively, that the ultimate destination that classical political economy leads us to in its own pursuit of explaining value is paradox. It is now up to Marx to take us beyond this impasse by taking us beyond the sphere of exchange and into the sphere of production. This he begins to do in Chapter Six...

For there to be a way out, Marx argues, there has to be a particular commodity out there on the market 'whose use-value possesses a peculiar property of being a source of value, whose actual consumption is therefore itself an objectification of labour, hence a creation of value'. And, indeed, there is such a commodity available to the 'possessor of money'. It is the 'capacity for labour, in other words labour-power'.

A capitalist purchases labour-power (the capacity for labour) from its seller, a worker. S/he then puts the worker to work in a process of production in which this use-value is consumed. The worker's labour-power is converted into energy and this energy is objectified within the product being made. It is in this act of labour that a worker's labour-power transfers new value into the commodity it is producing.

Marx goes on to identify certain social conditions that are necessary for the commodity labour-power to exist. The worker has to be free to alienate her labour and only for a limited period of time, otherwise she would be a slave. There has to be the legal institution of private property that recognises seller as owner and both buyer and seller of labour-power as equal under the law. Finally, and crucially, the seller of labour-power must have no other commodities to sell and must be 'compelled to offer for sale as a commodity that very labour-power which exists only in his living body'. What this means for the actual nature of freedom under capitalism is profound:

'For the transformation of money into capital, therefore, the owner of money must find the free worker available on the commodity-market; and this worker must be free in the double sense that as a free individual he can dispose of his labour-power as his own commodity, and that, on the other hand, he has no other commodity for sale, i.e. he is rid of them, he is free of all the objects needed for the realization [Verwirklichung] of his labour-power.'

In short, the worker in a capitalist mode of production - the seller of labour-power - is doubly free: She is free to work and she is free to starve!

Marx goes on to emphasise that these social conditions are, indeed, social and not natural. They are the outcome of particular historical conditions and that the mere existence of money and commodities are not enough. The capitalist mode of production 'arises only when the owner of the means of production and subsistence finds the free worker available, on the market, as the seller of his own labour-power. And this one historical pre-condition comprises a world’s history. Capital, therefore, announces from the outset a new epoch in the process of social production.'

Next, Marx spends several pages showing how the value of this special commodity, labour-power, like any commodity is determined by the amount of labour necessary to produce it. That is, the value of labour-power in any given society is determined by the commodities it takes for that worker to reproduce not just himself, but his family. This amount is historically specific and is determined not just by physical factors like the climate, but by 'civilizational' factors such as what in that society's culture is deemed necessary. Though he doesn't mention it directly yet, it will also be determined by the balance of power between the capitalist and proletarian classes. Hence, though this amount differs in every society and though it is constantly changing, it can be ascertained quantitatively. The best example to explain this concept, I think, is the measure of the poverty line and the politics of defining that poverty line in terms of calorific content, for example.

We're nearly there!...

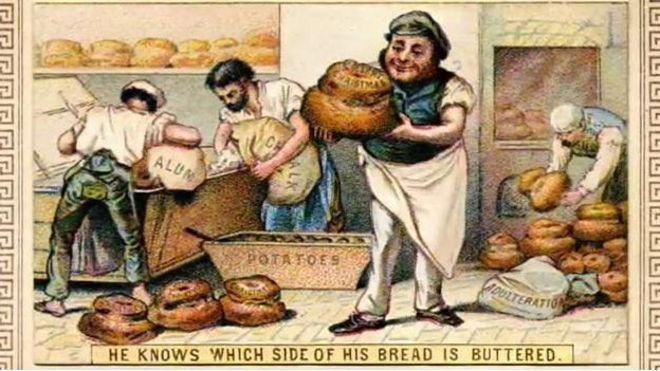

Marx then makes a really crucial point. Usually, when you are wanting to sell a commodity, you wouldn't consider selling it until you get the money for it. However, with labour-power, the worker sells the commodity in advance, i.e. she gets her wages only after she has done her work. With all the talk of the risk that entrepreneurs take on, we very rarely hear of the risk that workers take on each day, week, and month. In reality, when we work, we 'allow credit to the capitalist'. And this credit is 'no mere fiction'. This is shown 'not only by the occasional loss of the wages the worker has already advanced, when a capitalist goes bankrupt, but also by a series of more long-lasting consequences'. The long-lasting consequences Marx refers to are detailed in his footnotes. There he draws on various reports into the widespread sale and consumption of toxic, adulterated bread. This takes place because workers are impoverished by having to wait for low wages, so that they cannot afford to purchase decent, proper food ahead of payday.

We've gone with him through six chapters, but finally we come to understand where Marx has been leading us:

'The process of the consumption of labour-power is at the same time the production process of commodities and of surplus-value. The consumption of labour-power is completed, as in the case of every other commodity, outside the market or the sphere of circulation.'

The following passages are some of my most beloved in anything I have ever read anywhere:

'Let us therefore, in company with the owner of money and the owner of labour-power, leave this noisy sphere, where everything takes place on the surface and in full view of everyone, and follow them into the hidden abode of production, on whose threshold there hangs the notice ‘No admittance except on business’. Here we shall see, not only how capital produces, but how capital is itself produced. The secret of profit-making must at last be laid bare.'

We have to leave the busy market-place - the sphere of exchange - and venture into the 'hidden abode of production' in order to see not just how surplus-value, but capital itself is produced. Incidentally, Nancy Fraser wrote a great article in New Left Review a few years ago, arguing that there are multiple hidden abodes that are the 'background conditions of possibility' that make capital accumulation even possible. These are ecology, social reproduction (the daily labour of the household and of care), and the public realm.

Marx finishes with a flourish. First, he mocks liberal pretensions. The exchange in the market between buyer (capitalist) and seller (worker) of labour-power is held up in liberal writings to be the apotheosis of 'Freedom, Equality, Property, and Bentham': the two exchange freely and equally their own private property and (here's the Bentham bit) they do so motivated by their own self-interest. Nonetheless, whether it is 'in accordance with the pre-established harmony of things, or under the auspices of an omniscient providence' (mocking Adam Smith here!)' the outcome is apparently beneficial to 'their mutual advantage, for the common weal, and in the common interest'. Instead of this great liberal vision, Marx finishes with a more realistic depiction of the sale and purchase of labour-power...

'When we leave this sphere of simple circulation or the exchange of commodities, which provides the 'free trader vulgaris with his views, his concepts, and the standard by which he judges the society of capital and wage-labour, a certain change takes place, or so it appears, in the physiognomy of our dramatic personae. He who was previously the money-owner now strides out in front as a capitalist; the possessor of labour-power folllows as his worker. The one smirks self-importantly and is intent on business; the other is timid and holds back, like someone who has brought his own hide to market and now has nothing else to expect but - a tanning.'

Curtain closes on Act One! Sorry for the lengthy blog, but join us next week inside the hidden abode to see how surplus-value is produced!

Thanks for reading

Joel

Comments